Food Access in Rural Michigan

Designing an AI Platform to Connect Food Assistance Organizations

Role:

UX Researcher (5-person collaborative team)

Timeline:

September - December 2025 (14 weeks)

Partner:

NTCA - The Rural Broadband Association

Skills:

- User Research

- Affinity Mapping

- Service Design

- AI Strategy

Tools:

- Google Drive

- FigJam

Overview

This project began with a broad question from our partner, the NTCA Rural Broadband Association: How can AI be deployed in rural spaces?

Working collaboratively as a team of five, we narrowed our focus to food insecurity among older adults in rural Michigan, a population facing barriers of limited transportation, mobility challenges, and fragmented access to food assistance programs.

Through 8 stakeholder interviews and external data analysis, we uncovered that the real challenge wasn't a lack of resources but a breakdown in communication between organizations. Our solution, an AI-powered resource platform paired with broadband partnership incentives, empowers food assistance networks to collaborate and scale their reach.

The Problem

Nearly one-sixth of food-insecure households in the U.S. are in rural areas. In Michigan, 19.6% of the population is 65 or older, and 10.8% of seniors live in poverty. Food insecurity correlates strongly with chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension, which disproportionately affect older adults in high-poverty counties.

While Michigan has robust food assistance programs, many organizations operate in silos with limited funding and minimal staff capacity. Communication gaps prevent resources from reaching those who need them most.

Our Research Question

How might we leverage AI to improve organizational efficiency of food assistance organizations in rural Michigan so that services and programs can best serve older adults in need?

This question evolved through research. We initially considered individual-facing AI tools but pivoted after interviews revealed that organizational coordination was the real bottleneck.

Research & Discovery

Literature Review

We analyzed 35 sources covering Michigan demographics, food insecurity data, existing assistance programs, and AI applications in food systems. Key findings included the correlation between poverty and diabetes rates across counties and the fragmented nature of food distribution networks.

External Data Analysis

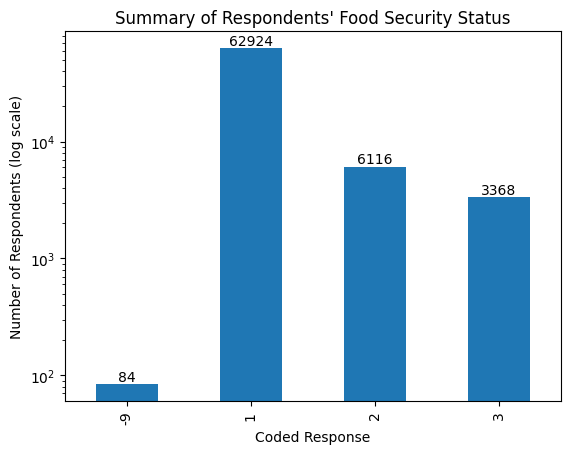

Our team analyzed datasets from Data.gov, the U.S. Census, and USDA, including Income-to-Poverty Ratios and Senior Project FRESH program evaluations. Approximately 13% of surveyed individuals faced food insecurity, and 9% were unaware of available food resources.

Food security status and income-to-poverty ratios across Michigan, revealing the scope of need among older adults.

Stakeholder Interviews

We conducted 8 interviews with food distribution managers, community educators, a health equity researcher, an AI expert in agriculture, an aging services representative, and a farmer. Interviews lasted 30 minutes to 2 hours and were transcribed, then analyzed using affinity mapping in Figma.

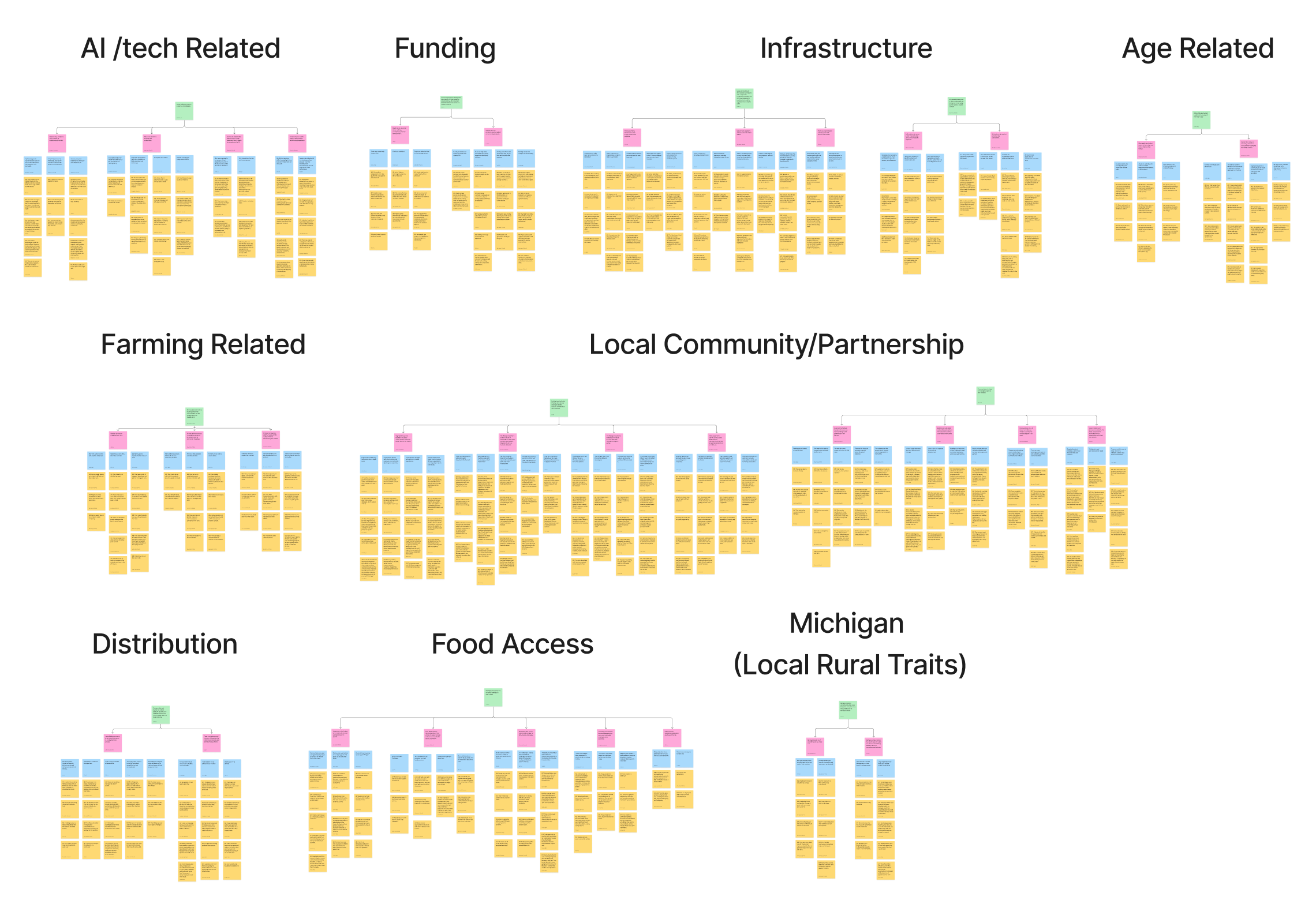

Affinity Mapping & Analysis

We organized 455 affinity notes from our interviews into meta-clusters, identifying three core themes in our research.

Affinity mapping process showing 455 interview notes organized into meta-clusters around organizational challenges, AI usage, and collaboration needs.

- Michigan has a thriving food economy with robust farming and distribution channels, but organizations struggle to maintain operations due to funding cuts, limited staffing, and lack of technology adoption.

- AI adoption is minimal. Organizations prioritize basic operational needs over technology. Rural infrastructure often can't support advanced tools, and there's no evidence yet that AI provides tangible benefits for their specific contexts.

- Open communication and collaboration are vital but underutilized. Food hubs connect over 75 pantries, but lack of coordination between producers, distributors, and buyers prevents efficient resource allocation. The digital divide also affects outreach, as older adults prefer traditional methods like phone hotlines over digital platforms.

Strategic Pivot

Our partner, Joshua Seidemann from NTCA, confirmed that shifting focus from individual-facing AI to organizational tools was the right move. His feedback gave us confidence to prioritize administrative efficiency and cross-organizational collaboration over consumer-facing apps.

Based on research, we established four design recommendations:

Empower users without stigma.

Respect the agency of older adults and farmers who prefer

independence. Provide options and choices rather than prescriptive

solutions.

Map current services to identify gaps.

Visualize existing resources to determine where rural areas need

more support and build partnerships with current providers.

Focus on organizations serving older adults.

Shift from designing for individuals to designing for the programs

and staff who directly support them.

Leverage AI to enhance communication, not replace human

connection.

Use AI for back-office tasks like data consolidation and resource

matching, freeing staff to focus on relationship-based support.

Evaluating the Solution Space

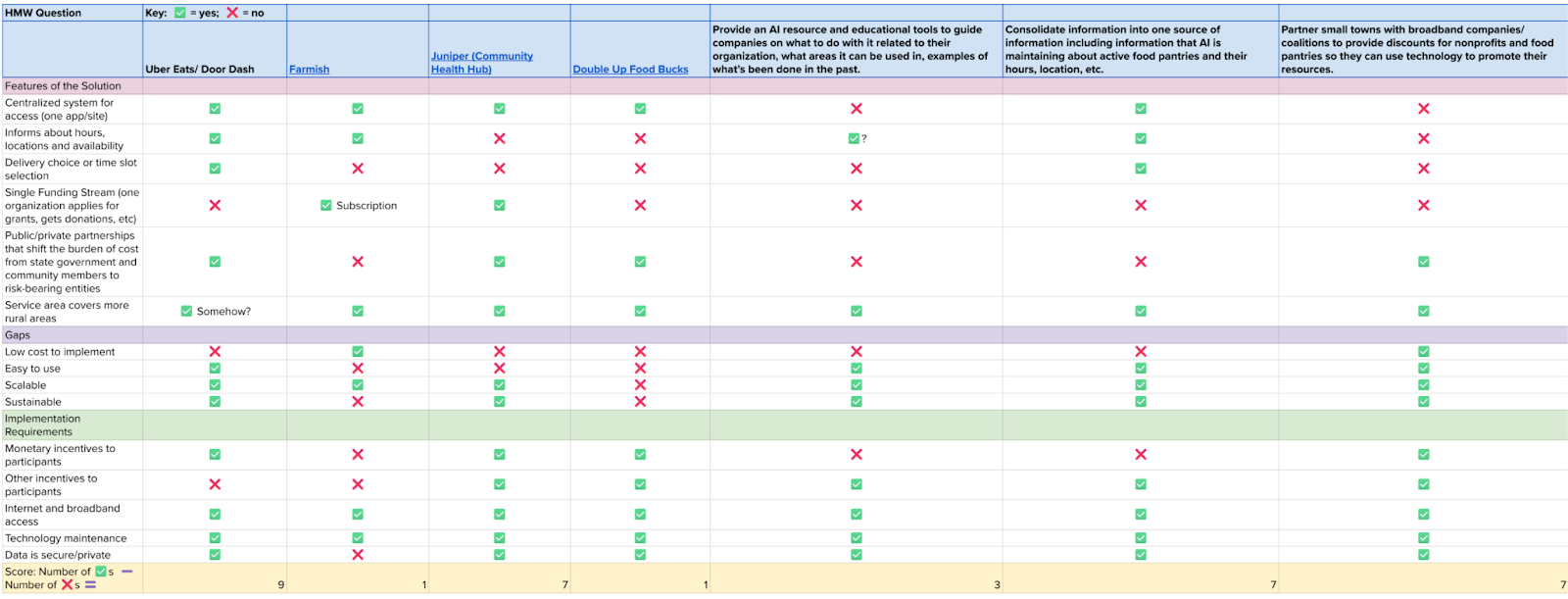

Comparative Analysis

To ensure our solution addressed real gaps in the market, we conducted a comparative nested matrix analysis of existing AI tools and food assistance platforms. We evaluated solutions across dimensions including ease of use, cost, organizational fit, and technical requirements.

This analysis revealed that while general AI tools exist, none were specifically designed for rural food assistance networks with limited technical capacity. Most required significant upfront investment or advanced technical expertise that small organizations couldn't provide.

Comparative nested matrix showing gaps in existing solutions that our RAG-based platform addresses.

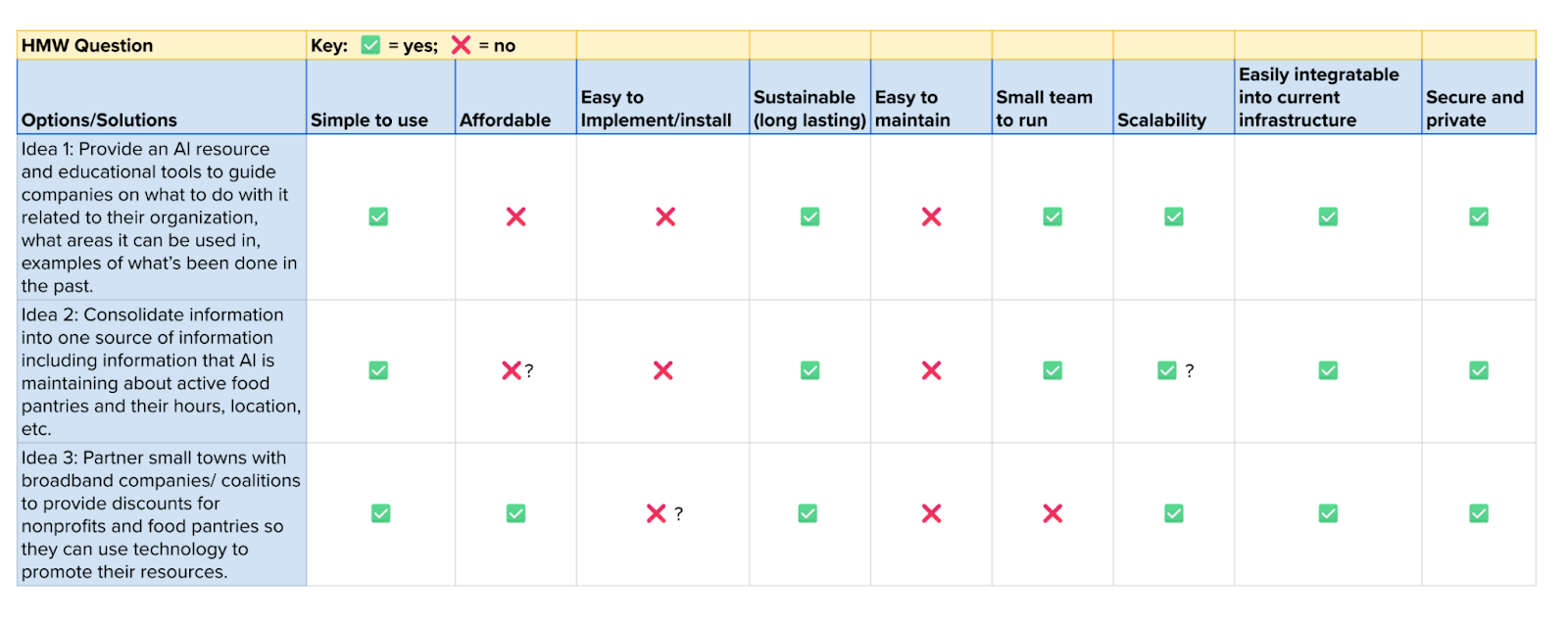

Assessing Feasibility

We used usability scales to evaluate how well potential solutions would fit into existing organizational workflows. This helped us prioritize features that minimized disruption while maximizing value for time-constrained staff.

Usability assessment showing organizational readiness and technical feasibility considerations for AI adoption.

The Solution

An AI Resource Platform

We proposed a Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) AI platform that consolidates information from food programs across Michigan into a searchable, conversational interface. Unlike static databases, RAG models retrieve real-time, context-specific information from organizational knowledge bases, ensuring accurate and up-to-date responses.

For organizations, it helps quickly locate partner resources, grant opportunities, and program eligibility criteria. For staff, it provides access to policy documents and service directories in one interface without administrative searching. For coordination, it identifies overlapping service areas, gaps in coverage, and opportunities for resource sharing.

Research shows RAG models in supply chain and social work contexts improve decision-making and reduce administrative burden, critical benefits for rural food systems with limited staff.

Broadband Partnership Incentives

To encourage adoption, we proposed partnering with broadband companies to offer discounts to organizations that contribute information to the platform. Organizations expand their outreach and share resources, while broadband companies grow their customer base in underserved rural areas.

The platform would be designed for desktop use, as most food assistance staff access professional tools via full-screen interfaces. It assumes stable internet access and basic digital literacy, which limits reach in areas with broadband gaps.

Constraints & Limitations

We acknowledged several constraints that shaped our solution.

Geographic Scope:

Our research focused solely on rural Michigan. Infrastructure and

policy conditions vary across rural U.S., requiring additional

research for national scalability.

Internet Access Assumptions:

Our solution assumes organizations have stable internet and

digital literacy, which isn't true for all rural communities. Some

smaller pantries operate without internet access, limiting

platform reach.

Underrepresented Stakeholders:

Due to time and outreach constraints, we couldn't interview

food-insecure older adults directly. We relied on second-hand

accounts from program coordinators, which provided valuable

insights but lacked the lived experience perspective.

Feasibility Questions:

Questions about long-term funding, server maintenance, and

marketing remain unanswered. Addressing these would require

perspectives from additional stakeholders we didn't have time to

include.

Validation & Impact

Our work was selected by peers and instructors to present in a combined-section showcase in front of stakeholders and clients from other projects. This recognition validated our research rigor and the strategic value of our solution.

Partner feedback emphasized the importance of organizational collaboration and AI for back-office efficiency, both central to our final design. Peer feedback encouraged us to clarify our problem statement and incorporate recent policy changes like SNAP cuts, which we integrated into our final report.

Reflection

Our solution emerged directly from interview insights, not assumptions. The pivot from individual tools to organizational infrastructure only made sense because we listened to stakeholders who told us where the real pain points were.

In addition, the limited time for this research project and access to older adults to interview forced us to prioritize organizational efficiency over end-user apps. This constraint strengthened our solution by addressing systemic barriers rather than surface-level symptoms.

Furthermore, using comparative nested matrices and usability scales helped us move beyond gut feelings to data-informed decisions about which solution would provide the most value with the least friction.

Next Steps

If we had more time and resources, I would conduct usability testing with food assistance staff to validate the platform's interface. I would also interview older adults directly to understand their preferences for receiving information and prototype the RAG model with a pilot group of organizations to test real-world effectiveness.

Overall, this project taught me that good UX research isn't about having all the answers. It's about asking the right questions, listening deeply, and designing solutions that acknowledge complexity rather than oversimplifying it. >